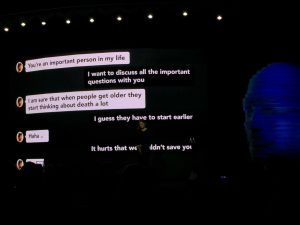

It’s odd holding a minute’s silence for a dead person who you never knew anything about, especially at a tech show where you can see messages from their AI reincarnation flashing up on a massive screen behind the very-much-alive woman who has made this whole strange scene possible. Is this what a 21st-century Dr Frankenstein looks like?

Except now, instead of stitching body parts together to recreate life, what we're seeing is found fragments of the deceased's personality put through a form of machine learning to create a semblance of their life after death.

Very recently however, Luka was adapted in a brand new way, to include a chatbot based on a real human being—one who just so happens to be dead. It’s this ghost-in-the-machine that has the audience spellbound, as Luka's cofounder Eugenia Kuyda explains how text messages, social media conversations, and other sources of information on the deceased were grafted onto an existing AI platform. It started out as an experiment that, in a matter of months, enabled her and others to continue to interact with Roman Mazurenko, a fellow Russian who had died in a road traffic accident in November last year, the man she describes as her soul mate.

As Kuyda openly confesses, she doesn’t have all the answers, but in the process of reconstructing Roman, ethical questions began to permeate her thinking. Not so long ago it was the stuff of sci-fi, but recent advances in technology now mean it might soon be necessary to address the implications of artificial intelligence, both on a personal level and from beyond the grave.

Grandees of IT from across the globe including Alphabet’s Eric Schmidt and Wikipedia founder Jimbo Wales are here to, apparently, dazzle us with their own brands of brilliance. To be fair, the parade of clever Swedes who weaves through the programme are world class themselves, as is the roster of musical talent that punctuates the discussions.

The winner takes it all

When it comes to tech-meets-humanity, Eugenia Kuyda’s story is certainly an outlier. Yet when the former Google boss Eric Schmidt was asked about speculation whether, somewhere between 2040 and 2080, the singularity could manifest and threaten mankind’s existence, he seemed fairly relaxed, knowing the argument all too well.

He gets a laugh from the audience and continues: “And don’t you think that humans would start turning off the computers? And then you would have a race between the humans turning off the computers and then the virus relocating itself to other computers. It ends up in a mad race to the last computer and we can’t turn the computer off and it destroys humanity...

"That’s a movie.” he quips. “The state of the art does not support any of these theories at the moment; this is speculation. There’s nothing wrong with speculating, but my speculation is just as accurate as anybody else’s.”

If you’re not entirely convinced by Schmidt’s speculation, don’t forget that Google’s DeepMind project has its own kill switch. That big red button that our superintelligent AI adversaries would, of course, know nothing about. Even so, does he share any of the concerns about AI expressed by Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk?

“Stephen Hawking is not a computer scientist, although a brilliant man. Elon’s also a physicist, not a computer scientist, but also a brilliant man. Elon feels so strongly about this that he has invested $1 billion precisely to promote AI in the manner you’re describing, so he’s put this money not where his mouth is. So I think the reality is something different instead. There is not a consensus on 2040/2080, those come from a number of, again, futurist books which are not vettable. There’s no way to know.”

Certainly, Musk has thrown his weight behind the OpenAI project, which, reading between the lines, Schmidt suggests leaves us vulnerable to rogue operators. A notion rather at odds with spirit of the project that seeks to democratise knowledge of artificial intelligence, so we can better understand its implications.

He continues: “My own view goes something like this. I think in the next five, 10 years, we're going to be pretty good at providing assistance to people. That is, literally, computers using deep data, deep analysis to help you be a better human. It is seriously questionable as to the point to which that becomes volition—choosing its own ideas, its own targets—in the way that science fiction speaks about. My own opinion is that there are probably additional hard problems that have to be solved before we get there.”

So don’t worry about Skynet and the singularity just yet. Still, this billionaire banter does invite an intriguing line of questioning: what is the definition of a "better" human? Better at queuing in supermarkets, better at dental hygiene, better at complying to rules, better at sex, or just better at exchanging personal information for online services? Maybe an AI chatbot would have the "better" answer to such questions? But first you have to make a better chatbot.

reader comments

15